(c) 2016 MJ Alternative Investment Research. All Rights Reserved.

Last week’s blog got me in a bit of hot water with some alternative investment folks I know. In fact, some thought it should have come with a lifetime supply of chocolate-covered Prozac to counteract the depressive, after-reading effects.

To answer the queries I seemed to receive en masse: No, I am not a defeatist. I am instead an optimistic pessimist – I’m often quite positive that the worst possible thing is bound to happen.

But just because I suggested last week that a few fund managers might have to (or want to) evaluate their long-term business viability in 2016 doesn’t mean I think this year is a total loss.

In fact, I’d say my best advice is, in the infamous words of Douglas Adams, “Don’t panic!” If you can do that and still somehow end 2016 knowing where your towel is, you’ve won.

But seriously, there are a number of positive developments for money managers that could play out this year. For example:

Market Volatility May Be Your Friend – If the stock market theme song post-financial crisis has been “Sweet Child of Mine”, 2016 has certainly changed its tune. Market volatility during the first two weeks of January brought me back to my high school-era living room, sitting in front of my (not flat-paneled) TV watching Axl Rose wiggle across stage belting out “In the jungle. Welcome to the jungle. Watch it bring you to your knnn, knnn, knnn, knnn, knees, knees. I want to watch you bleed!” That was one of my favorite videos back when, you know, MTV actually played music.

And while market volatility can be an exercise in white-knuckle, bile-producing, ‘how-will-I-ever-retire-now’ angst, it also offers investment managers an opportunity they haven’t really had since March 9, 2009: The chance to be a hero.

In a raging bull market, most performance looks like beta. No matter how well an active money manager does, the market can do it faster, cheaper and potentially better. A bull market is often a chump factory, no matter your talents.

And don’t get me wrong, I love a bull market because I am generally in better shape (shopping is, after all, my cardio), but a bull market doesn’t love active management. A down, sideways or otherwise volatile market creates what active money management really needs: Opportunity.

So play this one well, intrepid asset managers, and you could potentially see your breakthrough moment. And may the odds be ever in your favor.

The Fees Knees – Speaking of your knnn, knnn, knnn, knnn, knees, while the markets haven’t exactly been a jungle until recently, the fee debate certainly has. There has been a barrage of class action lawsuits against Fidelity, Vanguard and others about excessive 401(K) fees. And if you Google “hedge fund fees” two of the top three responses are “Hedge Fund Performance Fees Decline Sharply” (FT) and “The Incredibly Shrinking Hedge-Fund Fee” (Bloomberg View).

Due at least in part to the inability of active managers to shine (see above), fees have become a inevitable battle ground for investors. When the rising tide lifts all ships, it becomes easier to confuse price with value.

But market volatility may help successful managers overcome near militant fee resistance, and interestingly enough, a new lawsuit against Anthem Inc. about low fee funds may help traditional active managers as well.

“An overriding theme of lawsuits attacking 401(k) plan fees is that they generally view the cheapest investment as being the most prudent investment choice fiduciaries can make for plan participants, according to Brad Campbell, counsel at Drinker Biddle & Reath and former head of the Employee Benefits Security Administration. That, Mr. Campbell said, is inconsistent with a fiduciary's obligations under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, which indicates fees must be reasonable rather than the most inexpensive. According to the text of the new suit's complaint, “investment costs are of paramount importance to prudent investment selection,” which Mr. Campbell said is “an inaccurate statement of the law.” (http://www.investmentnews.com/article/20160112/FREE/160119984/401-k-suit-targeting-vanguard-fees-could-support-case-for-active)

After all, to misquote Brian Tracy, “The true measure of the value of any [money manager] is performance.”

Election Attention – And finally, in case y’all have slept through the proposed UK Trump ban, the Sanders-Clinton (oh, yeah, and O’Malley) poll mania, and impassioned pleas for walls around the country or just around Wall Street, you know we’re in an election year. Why is this a good thing? Well, for one, it’s wildly entertaining, although it does bring to mind PoliSci 401 “Those who seek power are not worthy of that power.” (Plato)

But really, it means the Eye of Sauron (read: regulatory and compliance entities) may be thinking about Wall Street, but it is unlikely that much will change this year, giving everyone a chance to continue working through compliance, operations, Form PF, AIFMD, and all of the other special gifts fund managers have gotten post 2008. Hell, someone may even come up with a way to streamline some of those processes during the short lull in activity and actually create some true economies of scale for struggling small funds. It’s MLK day (er, night) as I’m writing this so well, dammit, I have a dream.

In short, it ain’t all doom and gloom out there for the financial industry, but if this blog failed to convince you of that, I can only offer the following to answer any of your lingering doubts or questions.

42

As y’all recover from the excesses of fried turkeys, stuffed stockings, too much ‘nog and an overdose of family time, it seems like a good time to catch up on some light reading. So, in case you missed them, here are my 2015 blogs arranged by topic so you can sneak in some snark before you ring in the New Year.

Happy reading and best wishes for a joyous, profitable, and humorous 2016.

Happy Holidays from MJ Alts!

HEDGE FUND TRUTH ANIMATED SERIES

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/6/29/hedge-fund-truth-series-hedge-fund-fees

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/6/1/the-most-hated-profession-on-earth

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/3/2/the-hedge-fund-truth-launching-and-running-a-small-fund

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/1/19/savetheemergingmanager

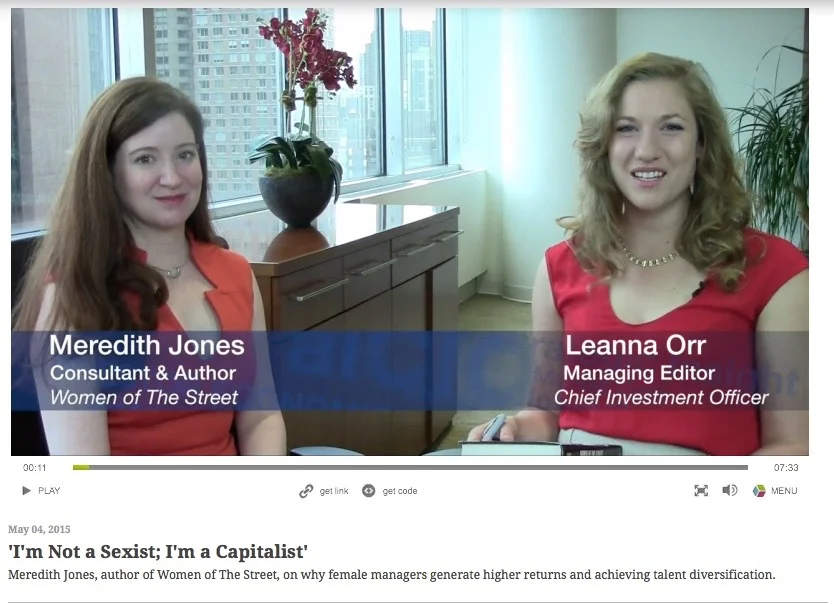

WOMEN AND INVESTING

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/12/13/dear-santa

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/11/16/not-so-fast-times-at-hedge-fund-high

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/9/25/doing-well-doing-good-improving-investment-diversity

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/7/26/the-evolution-of-a-female-fund-manager

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/6/10/advice-to-the-future-women-of-finance

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/4/27/diversification-and-alpha-by-the-book

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/1/26/dont-listen-to-greg-weinstein

EVERYONE HATES ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS (ESPECIALLY HEDGE FUNDS)

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/12/7/keen-delight-in-the-misfortune-of-hedge-fundsand-me

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/2/2/mfp1glk0exk0vlnqtpx6lby2ba9z8n

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/11/23/babelfish-for-hedge-funds-1

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/11/8/hedge-funds-bad-reputation

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/10/5/dear-hedgie

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/9/9/investment-professional-fact-fiction-the-business-trip

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/5/17/hedge-funding-kindergarten-teachers

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/4/14/are-hedge-clippers-trimming-up-the-wrong-tree

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/2/16/rampallions-scullions-hedge-funds-oh-my

FUND RAISING & INVESTOR RELATIONS

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/6/22/swingers-and-the-art-of-investor-communication

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/4/5/7-secrets-to-a-successful-fund-elevator-pitch

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/10/26/founding-funders

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/8/28/crisis-communication-for-investment-managers

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/7/20/trust-me-im-a-portfolio-manager

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/5/4/the-declaration-of-fin-dependence

EMERGING MANAGERS

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/8/17/people-call-me-a-skeptic-but-i-dont-believe-them

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/10/19/are-you-the-next-blackstone-dont-count-on-it

DUE DILIGENCE

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/11/1/the-evolution-of-due-diligence

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/8/6/a-little-perspective-on-the-due-diligence-process

GENERAL INVESTING INSIGHTS

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/10/11/investment-wisdom-increases-with-age-dance-skills-dont

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/8/24/the-love-of-the-returns-chase

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/8/2/slamming-the-wrong-barn-door

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/6/8/the-confidence-hubris-conundrum

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/5/10/the-crystal-ball-in-the-rearview-mirror

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/2/23/pattern-recognition-may-make-you-poorer

http://www.aboutmjones.com/mjblog/2015/1/5/new-years-resolutions-for-investors-managers-part-one

What do you want to read about in 2016? List topics you enjoy or would like to see more of in the comments section below.

In the meantime, gird your loins for the blog that always parties like it’s 1999, even when it’s 2016.

And please follow me on Twitter (@MJ_Meredith_J) for daily doses of research, salt and snark.

Those of you that have heard me speak on more than one occasion have probably heard me utter the phrase "Investing in emerging managers is like sex in high school. Lots of talk, very little action." In full disclosure, Jim Dunn of Verger was the first to utter those words, but they are so apropos that I have sense borrowed them for myself once or twice. (Thanks Jim!)

This week, I had the opportunity to informally poll investors and emerging managers, this time in the form of women-run funds, and that wonderful turn of phrase proved apt once again. In fact, I could almost hear Mike Damone saying "I can see it all now, this is gonna be just like last summer. You fell in love with that girl at the Fotomat, you bought forty dollars worth of [freakin'] film, and you never even talked to her. You don't even own a camera."

Indeed, it does seem as if investors often spend a lot of time stalking the camera store, but never getting the picture. So I decided to ask the audience of managers and investors at last weeks 100 Women in Hedge Funds Senior Practitioner Workshop where we stand and what could help the situation. Here's what I learned.

1) Some women-run funds may be getting lucky, but action is still sparse.

(c) 2015 MJ Alts

2) Managers feel that a number of things impede their ability to raise capital, but investors are focused primarily on only two issues: supply and size.

(c) 2015 MJ Alts

(c) 2015 MJ Alts

3) And the answer to what would make investing in women-run funds easier? Three words: Binders of Women. Just kidding, but better data sources for women-run funds, better consultant buy-in and the mysterious answer "other" all ranked pretty high. Some of the suggestions for "other" included more seed capital to help overcome AUM objections and more networking with managers you don't already know.

(c) 2015 MJ Alts

And, while these responses were specifically geared towards women owned and women run funds, in my conversations with investors, the issues are not entirely dissimilar for minority owned and run funds, or really any other emerging manager.

So, ladies and gentlemen, let's work the problem and see if there aren't good solutions to these issues. It will be healthy for me to have to come up with a new, creative and vaguely offensive way to describe the industry.

And please take a moment to support 100 Women in Hedge Funds as they are part of the solution and the reason I could run this quirky poll in the first place!

Less than one score and seven years ago, it was relatively easy for hedge funds and other private fund vehicles to gain early stage capital. They went to their networks of high net worth individuals, let a little word of mouth work its magic, and then waited for early investments to roll in. Due diligence was minimal, who you knew was paramount and a rising tide (the Bull Market) lifted all ships. If it hadn’t been for the shoulder pads, it might have been the golden age of hedge funds.

Now, of course, raising early stage capital is a whole different ballgame. From seeders to bootstrapping to joint ventures to Founders’ Share classes, there are a host of options available to emerging managers who want assets, although frankly most work better in theory than they do in practice.

Lately, most of the buzz has surrounded Founders’ Share capital. And for managers that are unable to secure bulk early stage financing from a seeder, founders’ shares may hold some appeal.

Founders’ shares generally reduce management fees by up to 50 basis points, while incentive fees may be reduced by up to 5 percent. Founders’ shares are generally offered for a limited time for only early mover investors and are discontinued when a specific asset level or time threshold is passed. Founders’ Shares, and their reduced fees, remain in effect as long as the investor maintains an allocation to the fund.

Founders’ Shares have a lot of perceived benefits, including:

- Founders’ Shares sound cool. Seriously. Investors feel more like they’ve build something, and that can be appealing to some.

- They create urgency. Because Founders’ Shares are only offered until a certain AUM threshold is reached, or for a certain period of time, theoretically this “limited time offer” should encourage investors to pull the allocation trigger. Hey, it works for Ronco...

- They entice fee-wary investors without sacrificing the entire fee structure of the fund.

However, just because they sound good in theory doesn’t mean they are a panacea for every fund.

- Managers should consider the capacity of the fund. If the capacity is low, the amount allowed in founders’ share classes must be balanced to prevent a general loss of profitability for the fund.

- Institutional investors who insist on a “most favored nation” clause may be eligible to receive the reduced fee structure. As a result, it is important to discuss any legal ramifications of founders’ shares with counsel.

- Marketing materials must be created that clearly outline the opportunity for early investors. These materials (as well as any databases to which you’ve reported fees) must be updated when the initial “founding period” is over.

Perhaps most importantly, it’s important to remember that sacrificing fee revenue is most dangerous when assets under management are low. Once a firm or fund has attracted $1 billion in AUM, even a 1% management fee will generate $10 million in fee revenues in a flat year. For a $100 million fund, that fee revenue falls to $2 million in a 2% and 20% scenario, and $1 million in a 1% and 20% scenario (assuming flat performance).

And of course, those numbers are BEFORE expenses. Citibank estimates that a typical $100 million hedge fund must spend $2,440,000 each year to keep the fund running. Factoring that into the equation, it’s easy to see how quickly a fund can go from hero to zero, particularly if performance doesn’t pan out.

(c) 2015 MJ Alts

So I said all that to say this. Founders’ Shares can be a great thing if used judiciously, but please do the math to determine how much of a great thing you can stand to offer.

During an unbelievable number of meetings with investors and managers, I hear the same two refrains:

“We’re looking for the next Blackstone.”

Or

“We think we’re the next Blackstone.”

It’s enough to make you wonder if such success is commonplace or if we’re all overreaching just a teeny bit.

Well, I’ve shaken my Magic Eight Ball and the answer is this, at least for newer funds: “Outlook Not So Good.”

Recently, on a boring Sunday afternoon, I decided to go through Institutional Investor’s list of the 100 largest hedge funds and figure out when each fund company launched.

Yes, clearly I need more hobbies.

But the results (as well as my lack of social life) were pretty shocking. There are no funds within the top 100 that launched during the last 5 years. There are only 4 funds in the top 100 that launched within the last 10 years. In fact, nearly 70% of the top 100 hedge fund firms launched before the first iPod.

Obviously, this begs a question: Where are all the new Blackstones?

(c) 2015 MJ Alts

Whatever complaints can be lobbed at hedge funds, I do find it hard to believe that the talent pool has deteriorated to such a degree that there just isn’t a supply of skilled fund managers available. On the other hand, I do have a few theories on what forces may be at work.

- Change In Investor Dynamics: For a long time, hedge funds were the investment hunting ground of high net worth individuals and family offices. In fact, pre-1998 saw little to no meaningful investment of institutional capital into hedge funds, and investment activity into hedge funds didn’t accelerate markedly until after the Tech Wreck. But by 2011, 61% of all capital in hedge funds was institutional capital. But why should this matter? Imagine you’re an institutional investor with $1 billion or more to invest into hedge funds. Imagine you have a board. Imagine you have headline risk. Imagine you are hit on by every fund marketer known to man if you go to a conference. Imagine you have policies that dictate the percent of assets under management that your allocation can represent. Now, try to put that capital to work in a reasonable number of high-performing hedge funds. It seems reasonable to assume that the investing constraints of being a large institutional investor would drive allocations towards larger funds with longer track records. Just like you never get fired for buying IBM, it’s unlikely you’ll be canned for investing with Blackstone, AQR, Credit Suisse or other big name fund complexes.

- Market Timing: According to HFR, assets in hedge funds grew from $490.6billion in 2000 to nearly $1.9 trillion in 2007, or more than 287%. One of the reasons for this surge in assets is, I believe, prevailing market conditions. Having just exited one of the greatest bull markets in history and entered two of only four 10-year losing streaks in the history of the S&P 500, hedge funds had an opportunity to well, hedge, and as a result, outperform the markets. Unlike the last 6-ish years (recent months notwithstanding), where hedge funds have been heavily criticized for “underperforming” during an almost unchecked market run-up, market conditions were more favorable to hedged strategies between 2000 and 2008. This allowed managers with already established track records and AUM to capitalize on market and investor demographic trends and secure their dominant status going forward.

- Evolving Fund Management Landscape: Let’s face it – the financial world was a kinder and gentler place before 2008. Ok, that’s total BS, but it was less regulated. Hedge funds were not required to register with the SEC, file Form PF, hire compliance officers, have compliance manuals, comply with AIFMD, FATCA and a host of other regulatory burdens. As a result, firms formed prior to 2005 did perhaps have an overhead advantage over their newer brethren. Funds today don’t break even until they raise between $250 and $350 million in AUM, and barriers to entry have certainly grown. Add to this that more than 90% of capital has gone to funds with $1billion+ under management post-2008 and a manager would practically have to have perfectly aligned stars, impeccable performance and perhaps have made some sort of live sacrifice to achieve basic hedge fund dominance, let alone titan status.

This is not to say that newer funds haven’t made it into the “Billion Dollar Club” or that rarified air of 500 or so hedge funds that manage the bulk of investor assets. It is, however, a stark look at how we define expectations and success on both the investor and manager side of the equation. If 40 is the new 30 and orange is the new black, is $500 million or $1 billion in AUM the new yardstick for hedge funds? Time will tell, but I’m wondering if the Magic 8-Ball isn’t on to something.

As I prepare to move from one demographic checkbox to another later this week, I’ve been spending a fair amount of time wandering down memory lane. I’ve re-watched the movies from my youth, including Sixteen Candles, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Caddyshack and Smokey & The Bandit. I’ve gotten in touch with my inner Carlton Banks during a stirring, post-wedding live band rendition of “Footloose.” And I’m pretty sure when Loggins sang “everybody cut, everybody cut, everybody cut Footloose!” he wasn’t talking to me.

I’ve also spent a lot of time thinking about all the things I know now and all the stuff I have yet to learn.

For my 45th year, I plan to keep learning as much as possible. I’m going to surf camp for a week. I will finally learn how to do a proper figure skating sit spin. I vow to discover how to drive with more limited use of my middle finger. And of course, I hope to continue to figure out how to be a better investor, researcher and snarky advocate for the alternative investment industry.

When reflecting on what I do know I know, however, I did come up with some truths that constantly guide my investment decisions and unsolicited advice. They’ve become the North Star of my investment world, so to speak. And as luck would have it, there’s exactly one for each decade, with one to grow on. How fitting!

One: Continuous outperformance is a myth. Every manager screws up, gets caught with their portfolio pants down, or otherwise loses money from time to time. Finding the managers that minimize those downturns, can admit to and learn from mistakes, doesn’t keep making the same mistakes and, perhaps most importantly, live to invest another day is the real trick. Frankly, the only managers I’ve ever seen that never posted losses were frauds or, um, otherwise a bit creative in how they marked their portfolios.

Two: Between investing early and late, I’ll take early any day. In 2006, I started researching the outperformance of emerging managers. In 2010, I started researching women and minority run funds. Thus far, investors have largely ignored those groups in favor of the same old, same old. As an investor friend of mine once quipped: “Investing in emerging managers is like sex in high school, even though everyone talks about it, no one actually does it.” Despite the lack of investors putting their money where my mouth is, I remain convinced there’s significant alpha to be had with these groups. The lesson? Just because the packaging doesn’t look familiar doesn’t mean there’s not goodies inside. The same thing goes for new trends for venture capitalists, out-of-favor investments, sectors or strategies. Early bird, meet worm.

Three: Any way you can invest involves risk. Whether you keep money in a checking account, invest in hedge funds, index funds, actively, passively, in real assets, conservatively or aggressively, there is a risk you will lose money or not make enough money, or that you will not have access to your money or otherwise lose out. My Grannie kept money stuffed in the pockets of the clothes in her closet because she thought that was risk free, but she missed out on any potential profits and, obviously, her returns lagged inflation. Not to mention: what if the house burned down? There are no risk-free investments. Period.

Four: Investment professionals (and anyone else) that truly want to rip you off will find a way to do so. Having said that, the best way for them to accomplish that is to build blind trust. After all, the “con” in con artist is short for confidence. Most of the big scams in investing couldn’t happen without trust, and most of the time those closest to the bad actor are the first to get victimized. Think Bernie Madoff who bilked members of his religious community and other friends and family. Obviously, you need to trust your investment professionals by all means or you’ll never sleep at night, but never forget to at least periodically verify.

And one to grow on: Look out for zebras, but don’t forget about the horses. A recent venture capital fraud case involved not a sophisticated cyber fraud or complex skimming techniques. The perpetrator merely added a “1” to a check, changing $8 million to $18 million. Occam wasn’t wrong: It’s not always the most sophisticated schemes or black swans that cause losses. Sometimes the ordinary can be just as dangerous.

What’s the biggest lesson you’ve learned in your investing career? Feel free to sound off in the comments below with your best advice. And please follow me on Twitter (@MJ_Meredith_J) if you prefer your snark in 140 characters or less.

I’m a data nerd. I know it. You know it. It’s not like it’s a big secret. My name is Meredith Jones, and I let my geek flag fly.

So it’s no wonder that my nerdy spidey senses tingled late last week and early this week with the release of two new hedge fund studies. The first was eVestment Alliance’s look at small and young funds - version 2.0 of the emerging manager study I first launched at PerTrac in 2006. The second study, authored by hedge fund academic heavy weights Andrew Lo, Peter Lee and Mila Getmansky, looks at the impact of various database biases on aggregate hedge fund performance.

Neither paint a particularly bright picture of the overall hedge fund landscape.

So why aren’t I, Certified Data Nerd and long-time research of hedge funds, rolling around on the floor in piles of printed copies of each study right now? Because, in addition to being a total geek when it comes to a good pile of data, I’m also a big ol’ skeptic, and never moreso than when it comes to hedge fund data.

Here’s the thing, y’all. Hedge fund data is dirty. Actually, maybe even make that filthy. It's "make my momma want to slap me" dirty. Which is why it is critical to understand exactly what it is you may be looking at before jumping to any portfolio-altering conclusions. Some considerations:

One of the reasons I imagine Lo et al undertook their latest study was to show just how dirty hedge fund data is. They looked at backfill bias and survivor bias primarily, within the Lipper Tass database specifically. Their conclusion? When you adjust for both biases, the annualized mean return of hedge funds goes from 12.6% to 6.3%.

Ouch.

However, let’s consider the following:

No hedge fund database contains the entirety of the hedge fund universe. A 2010, comprehensive study of the hedge fund universe (again, that I completed for PerTrac) showed that 18,450 funds reported performance in 2009. Generally speaking, hedge fund databases cover roughly 7,500 or fewer “live” hedge funds. So, no matter what database you use, there is sample bias from the get go.

And while backfill bias and survivor bias do exist, so does participation bias.

Because a fund’s main motivation to participate in a hedge fund database is marketing, if a fund does particularly poorly (survivor bias) or particularly well (participation bias) it may stop reporting or it may never report. For example, of the top ten funds identified by Barron’s in 2014, three don’t report to Lipper Tass, two are listed as dead, two more aren’t reporting current data and three do report and are current. This could be sample bias or it could be participation bias. Hell, I suppose it could be survivor bias in some way. In any case, it does show that performance gleaned from hedge fund databases could be artificially low, not just artificially high.

As for emerging manager studies – they run into a totally different bias – one I’ll call barbell bias.

Unfortunately, due to wildly unbalanced asset flows over the last five years towards large funds, 85% of all hedge funds now manage less than $250 million. More than 50% of funds manage less than $100 million. Indeed, the hedge fund industry looks a little bit like this:

Some of you may remember my “Fun With Dots” blog from a few months ago. Using that same concept (each dot represents a hedge fund, each block has 100 dots and each line 1,000 dots, for a total of 10,000 dots, or funds) the Emerging vs. Emerged universe looks like this:

(c) MJ Alts

What’s interesting about this is, at least mathematically speaking, every fund in the large and mid sized category could have been outperformed by a smaller fund counterpart, but because of the muting effect that comes from having such a large bucket of small funds, the small fund category could still underperform.

Now, of course, I still found both studies to be wildly interesting and I recommend reading both. Again: Nerd. I also know that people have poked at my studies over the years as well, which, frankly, they should. Part of the joy of being a research nerd is having to defend your methodology. In addition, most people do the best they can with the data they’ve got, but it’s not for nothing that Mark Twain stated there are “Lies, damn lies and statistics."

What I am saying is this: Take all studies with a grain of salt. Yes, even mine.

In hedge funds - perhaps more than anywhere else, your mileage may vary. You may have small funds that kicked the pants off of every large fund out there. Your large funds may have outperformed your emerging portfolio. You may have gotten closer to 12% than 6% across your hedge fund universe (or vice versa). Part of the performance divergence may come from the fact that it’s hard to even know what the MPG estimates should be in the first place, which is why it’s critical to come up with your own return targets and expectations and measure funds against those indicators and not industry “standards.”

Sources: Barron's, CNBC, Bloomberg, LipperTass, MJ Alts, PerTrac, eVestment Alliance

Thinking about a hedge fund investment? Concerned about high fees? Before you request a fee reduction, consider that there isn't a "one size fits all" approach to fee structures. Fee reductions for smaller funds may introduce significant business risks and create counterproductive incentives. Fee reductions for larger funds may be desirable and more sustainable, but are also likely to be in shorter supply and may create negative selection bias. In short, investors AND managers should weigh the costs and benefits of slashing fees before they get themselves into an investing pickle.

For those of you that were fans of the movie Swingers you may remember this infamous scene:

“[It's 2:32am, and Mike decides to call Nikki, a girl he met just a few hours ago][Nikki's machine picks up: Hi, this is Nikki. Leave a message]

MIKE: Hi, uh, Nikki, this is Mike. I met you at the, um, at the Dresden tonight. I just called to say that I had a great time... and you should call me tomorrow, or in two days, whatever. Anyway, my number is 213-555-4679 -

[the machine beeps. Mike calls back, the machine picks up]

MIKE Hi, Nikki, this is Mike again. I just called cuz it sounded like your machine might've cut me off when I, before I finished leaving my number. Anyway, uh, and, y'know, and also, sorry to call so late, but you were still at the Dresden when I left so I knew I'd get your machine. Anyhow, uh, my number's 21 -

[the machine beeps. Mike calls back; the machine picks up again]

MIKE: 213-555-4679. That's it. I just wanna leave my number. I didn't want you to think I was weird or desperate, or... we should just hang out and see where it goes cuz it's nice and, y'know, no expectations. Ok? Thanks a lot. Bye bye.

[a few more calls. Mike walks away from the phone... then walks back and calls again; once again, the machine picks up]

NIKKI: [picks up] Mike?

MIKE: [very cheerful] Nikki? Great! Did you just walk in or were you listening all along?

NIKKI: Don't ever call me again.

[hangs up]”

Yeah, communicating with potential investors can feel a bit like that.

In fact, a few years ago I was speaking with an investor friend in Switzerland about manager communication. I asked him how much he liked to hear from his current managers and potential investments and, as was his wont, he laconically answered “Enough.” When I pressed him a bit further, he provided a story to illustrate his point.

“There is a manager that I hear from every day it seems. Every time I open the mail or get an email or answer the phone, I know it must be them. Finally, I started marking ‘Deceased’ on everything they sent and sending it back. Eventually the communication stopped.”

Seriously, when you have to fake your own death to escape an aggressive fund marketer, they’ve probably gone just a HAIR too far, donchathink?

All kidding aside, communication (how much and how often) is a serious question, and one that I get a lot from fund managers, particularly those frustrated with a lack of progress from potential investors.

While some managers react to slow moving capital-raising cycles by reducing or ceasing all communication (bad idea!), others move too far in the other direction, potentially killing (hopefully just figuratively) their prospects with emails, letters, calls, etc. But there is a happy medium for investor communication if you follow these simple guidelines.

Early communication – In the earliest days, just after you’ve met a new potential investor, your goals for communication are simple:

- Provide key information about the fund (pitch book, performance history);

- Attempt to schedule a meeting (or a follow up meeting) to discuss the fund in person;

- Establish what additional materials the prospect would like to see (DDQ, ongoing monthly/quarterly letters, audits, white papers, etc.)

- Send those materials

Your only goal at this stage is to see if you can move the ball forward to get to a meeting or a follow up meeting. Think of it like dating. Just not like Swingers dating. You always want to try to move the ball down the field, with the realization that being overzealous is more likely to get you slobberknockered than a touchdown.

Ongoing communication – After you have established a dialog with a potential investor, you should have realized (read: ASKED) what that investor wishes to receive on an ongoing basis. You should continue sending that. In perpetuity. Unless they ask you to stop, or they literally or figuratively die. Think about how much communication that an investor receives from the 10,000 hedge funds, 2,209 private equity funds, and 200+ venture capital funds that are actively fundraising. If your fund falls completely off the radar, how likely is it than an investor will think about you down the line? Yeah, them ain’t good odds. Your ongoing communication should consist of a combination of the following:

- Monthly performance and commentary;

- White papers (educationally focused);

- Invitations to webinars or investor days that you are hosting or notifications about where you will be speaking;

- Email if you are going to be in the prospects’ vicinity to see if an additional meeting makes sense.

In addition, it is a good idea to establish an appropriate time to call during your meetings. For example, after the initial or follow up meeting, ask specifically when you should follow up via phone. And then do it – no ifs, ands or buts. Even if performance isn’t great at the moment. Even if you feel you’ve now got bigger fish to fry. Make the call. And during that call, make an appointment for another call. And so on and so on and so on.

The trick here is to keep the fund in front of a potential investor without being in their face. And to do that, you MUST ask questions and you must be prepared to hear that another call and/or meeting may not make sense at the moment. Take cues from potential investors. Trust me, they’ll appreciate you for it.

During Due Diligence – If you are lucky enough to make it to the due diligence stage, I would suggest preparing a basic package of materials that you can send to expedite the process and demonstrate a high level of professionalism.

- AIMA approved DDQ – And don’t leave out questions. We’ve all seen these enough to know when questions have been deleted. If a question isn’t applicable put in N/A.

- References

- Audits (all years since inception)

- Biographies of principals

- Organization chart

- Offering documents

- Articles of incorporation

- Investment management agreement

- Information about outside board members

- Service provider contacts

- Valuation policies (if applicable)

- Form ADV (I and II)

After The Investment – After an investor makes an investment in your fund you should stay focused on your communication strategies. Ideally, you should agree with the investor BEFORE THE WIRE ARRIVES what they wish to see (and what you can provide) on an ongoing basis. This will help avoid problems in the future. You can earn bonus points by including any ODD personnel on materials related to operational due diligence, since they don’t always get shared between IDD and ODD departments.

Also, make sure you pick up the phone when performance is particularly good OR particularly bad. Many managers will call when performance is bad for advance “damage control,” but only calling when performance is bad creates a negative Pavlovian response to caller ID. Don’t be the fund people dread hearing from.

Hopefully these guidelines will help as you navigate the fundraising cycle. And if not, hey, Swingers quote.

Sources: IMDB.com, CNBC, NVCA

Given that one of the hedge fund industry's largest events takes place this week (SALT), that the Sohn 2015 event featured an emerging manager session and that it's just capital raising season in general, I thought it might be appropriate to share a little unsolicited fund marketing advice in this week's blog.

All too often, I hear about breakdowns in fund marketer/fund management relations. Fund management becomes disenchanted with how the asset raising process is going (read: slowly). Fund marketing feels pressured to raise assets for a fund that isn't performing well (read: poorly). Fund management feels that they (their three year old child, their neighbor's teenager or the guy on the street corner) could do a better job of bringing in capital. Fund marketing feels unappreciated (duped or downright angry) when bonus time rolls around.

It doesn't have to be this way.

To help avoid these common problems, I've put together a Declaration of Fin-Dependence. It's always important to remember that capital raising is not a solo sport and, even though I've seen it come to this, it ain't a contact sport either. In order to achieve capital raising success ($1 BEELION dollars, world domination, Rich List, etc.), it is critical that management and marketers both set and manage expectations carefully and execute on their common goals. The less ambiguity, the better. So, take a moment to read this historic document and then think about adding your John Hancock before you go after the Benjamins.

The Declaration of Fin-Dependence

I am no stranger to making lame excuses. Just last week, in the throes of a bad case of the flu, I managed to justify not only the eating of strawberry pop-tarts and Top Ramen but also the viewing of at least one episode of “Friday Night Lights.” It’s nice to know that when the chips are down at my house, I turn into caricature of a trailer park redneck.

But in between bouts of coughing and episodes of Judge Judy, however, I did manage to get some work done. And perhaps it was hyper-vigilance about my own excuse making that made me particularly sensitive to the contrivances of others, but it certainly seemed like a doozy of a week for rationalizations. Particularly when it came to fund diversity in nearly every sense of the term, but particularly when it came to investing in women and/or small funds.

So without further ado (and hopefully with no further flu-induced ah-choo!), here were my two favorite pretexts from last week.

Excusa-Palooza Doozie #1 – “We want to hire diverse candidates, but we can’t find them.”

In an interview with Fortune magazine, Marc Andreessen, head of Andreessen Horowitz said that he had tried to hire a female general partner five whole times, but that “she had turned him down.”

Now c’mon, Mr. Andreessen. You can’t possible be saying that there is only one qualified female venture capital GP candidate in the entire free world? I know that women only comprise about 8-10% of current venture capital executives but unless there are only 100 total VC industry participants, that still doesn’t reduce down to one. Andreessen Horowitz has within its own confines 52% female employees, and none of them are promotable? If that’s true, you need a new head of recruiting. Or a new career development program. Or both.

But it seems that Andreessen isn’t entirely alone in casting a very narrow net when it comes to adding diversity. A late-March Reuters piece also noted that they best way to get tapped to join a board as a woman was to already be on a board. One female board member interviewed had received 18 invitations to join boards over 24 months alone.

It seems the criteria used to recruit women (and, to some extent, minority) candidates into high-level positions are perhaps a bit too restrictive. In fact, maybe this isn’t a “pipeline” problem like we’ve been led to believe. Maybe it’s instead more of a tunnel vision issue.

So, as always happy to offer unsolicited advice, let me put on my peanut gallery hat. If you genuinely want to add diversity to your investment staff, here are some good places to look:

- Conferences – The National Association of Securities Professionals, RG Associates, The Women’s Private Equity Summit, Opal’s Emerging Manager events, the CFA Society, Morningstar and other organizations are all now conducing events geared towards women and minority investing. Look at the brochures and identify candidates. Better yet, actually attend the conference and see what all the hubbub is about, bub.

- Word of mouth – I have to wonder if Andreessen asked the female GP candidate on any of his recruitment attempts if she knew anyone else she could recommend. If not, shame on him. Our industry is built in large part on networking. We network for deals, investors, service providers, market intelligence, recruiting, job hunting, etc. We are masters of the network (or we should be) and so it seems reasonable that networking would be a fall back position for anyone seeking talent. And if Andreessen did ask and was not given suitable introductions to alternate candidates, shame on the “unnamed woman general partner.”

- Recruiters – Given the growing body of evidence that shows diversity is good for investors, it’s perhaps no surprise that there are now at least two recruiters who specialize in diversity candidates within the investment industry. Let them do the legwork for you for board members, investment professionals and the like.

- Service providers – Want a bead on a diverse CFO/CCO – call your fund auditor. Looking for investment staff? Call your prime broker or legal counsel. Your service providers see lots of folks come in and out of their doors. Funds that didn’t quite achieve lift off, people who are looking for a change, etc. – chances are your service providers have seen them all and know where the bodies are buried. Don’t be afraid to ask them for referrals.

Excusa-Palooza Doozie #2 – See?!? Investors are allocating to “small” hedge funds! In a second article guaranteed to get both my fever and my dander up, we were treated to an incredibly optimistic turn of asset flow events. It turns out that “small” hedge funds took in roughly half of capital inflows in 2014, up from 37% in 2013 per the WSJ.

Now before you break out the champagne, let me do a little clarification for you.

Hedge funds with $5 billion or more took in half of all asset flows.

Everything that wasn’t in the $5 billion club was termed “small” and was the recipient of the other half of the asset inflows.

It would have been interesting to see how that broke down between funds with $1 billion to $5 billion and everyone else. We already know from industry-watchers HFR (who provided the WSJ figures) that 89% of assets went to funds with more than $1 billion under management. We also already know that there are only 500 or so hedge funds with more than $1 billion under management. So really, when you put the pieces together, aren’t we really saying that hedge funds with $5 billion or more got 50% of the asset flows, hedge funds with $1 billion to $5 billion got 39% of the remaining asset flows, and that truly “small” and, well, "small-ish" hedge funds got 11% in asset flows?

I mean, for a hedge fund to be termed “small” wouldn’t it have to be below the industry’s median size? With only 500 hedge funds at $1 billion or more and 9,500 hedge funds below that size, it seems not only highly unlikely but also mathematically impossible that the median hedge fund size is $5 billion. Or $1 billion. In fact, the last time I calculated the median size of a hedge fund (back in June 2011 for Barclays Capital) it was - wait for it, wait for it - $181 million.

And I’m betting you already know how much in asset flows went to managers under that median figure…somewhere just slightly north of bupkis. And the day that hedge funds under $200 million get half of the asset flows, I will hula hoop on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

So let’s do us all a favor and stop making excuses and start making actual changes. Otherwise, we’re leaving money and progress on the table, y’all.

Sources: WSJ, HFR, BarclaysCapital, Reuters, Huffington Post

Regular readers of my blog know that periodically I offer completely unsolicited fund marketing advice. Given that we are in the midst of a busy conference season, I thought it wise to focus this week's peanut gallery on the elevator pitch. If you've been to many conferences in any capacity, you've had the opportunity to witness the elevator pitch in all of its flavors - the good, the bad, and the practically sociopathic. You may have even been asked (out loud or with just a frantic glance across a crowded cocktail party) to aid and abet the escape from an elevator pitch gone wrong.

To protect conference goers everywhere from the out-of-control elevator pitch, I've created the following infographic to help bring cosmos to the pitching chaos. I hope the advice will help your next asset raising encounter or at least make a colorful liner for your trash bin. As always, may the pitch be with you.

(c) MJ Alternative Investment Research LLC

When most people think about math, they don’t necessarily think about visual aids. They think about numbers. They think about symbols. They may even think, “Oh crap, I hated math in high school.” Even if you are in the last camp, read on. I promise what follows is painless, although you may be tested on it later.

A lot of times, what’s problematic for people about math is that picturing and therefore connecting with what we’re talking about, particularly when dealing with large numbers, can be difficult. For example, I talk endlessly about the inequities in the hedge fund industry, and yet while some folks hear it, I’m not sure how many people “get it.” So today, we’re going to “connect the dots” to visualize what is going on in hedge fund land.

First, meet The Dot Fund, LLC.

This dot represents a single, average hedge fund. The fund probably has a pitch book that states its competitive advantage is its "fundamental bottoms up research." This makes me want to shake the Dot Fund. But I digress.

Now, most folks estimate that the hedge fund universe contains 10,000 funds, so here are 10,000 dots. Each smaller square is 10 dots by 10 dots, for a total of 100 dots, and there are 10 rows of 10 squares. Y’all can count them if you want to – I did and gave myself a wicked migraine – but this giant square of dots is pretty representative of the total size of the hedge fund universe.

The Hedge Fund Universe

Of course, the hedge fund universe isn’t as homogenous as my rows of dots, so let’s look at some of the sub-categories of funds. The blue dots below represent the “Billion Dollar Club” hedge funds within the universe. That is not a ton of dots.

The Billion Dollar Club Hedge Funds

And here are the Emerging Managers, as defined by many pension and institutional investors as having less than $1 billion in assets under management. Note: That’s a helluva lot of blue dots.

Institutionally Defined “Emerging Managers”

This is the universe of managers with less than $100 million under management, or what I would call the “honestly emerging managers.”

Managers With Less Than $100m AUM

This dot matrix represents the average number of hedge funds that close in any given year. It doesn’t look quite as dire as the numbers do in print...

Annual Hedge Fund Closures

Finally, here are the women (stereotypically in pink) and minority owned (in blue) funds that I estimate exist today.

Diversity Hedge Funds

While estimates of capital inflows vary, eVestment suggests roughly $80 billion in asset flows for 2014, while HFR posits $88 billion. Because the numbers are fairly close, I'm using HFR, but the visual wouldn't be vastly different if I used another vendor's estimate. Here is the HFR estimate of $88 billion in asset flows represented as 1 dot per $1 billion.

2014 Estimated Asset Flows into Hedge Funds

Now, here is the rough amount of those assets (in blue) that went to the Billion Dollar Club hedge funds (also in blue).

Fund Flows Into Large Hedge Funds

And here is the rough proportion of those assets that went to everyone else.

Fund Flows Into Emerging Hedge Funds

Not a pretty picture, eh?

So, what’s the point of my dotty post? While I think we all have read about the bifurcation of the hedge fund industry into assets under management “haves” and “haves nots,” I’m not sure everyone has actually grasped what’s going on. I’m told that a picture is worth a 1,000 words, so maybe this will help it sink in. Not investing in a more diverse group of managers creates a very real risk of stifling innovation and compromising overall industry and individual returns. It also creates a lot of concentration risk - if a Billion Dollar Club fund fails, a large number of investors and a huge amount of assets could be at risk.

And the kick in the pants? We know this pattern isn't the most profitable. A recent study showed pension consultants underperformed all investment options by an average of 1.12% per year from 1999-2011, due largely to focusing on the largest funds and other "soft factors." And lest you think 1.12% sounds small, let me illustrate that for you, too. Here are one million dots, where each dot represents a dollar invested. The blue dots are the cash returns over time that were missed by not taking a more differentiated approach. Ouch.

Cash Return Differential 1999-2011

Luckily, the cure is simple. Commit to connecting with different and more diverse dots in 2014.

Sources: HFR, eVestment, MJ Alts, Value Walk, "Picking Winners? Investment Consultants' Recommendations of Fund Managers" by Jenkinson, Jones (no relation) and Martinez.

William Shakespeare once asked, “What’s in a name?” believing, as many do, that “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” But on this point I must take issue with dear William and say instead that I think names have power. Perhaps this notion springs from being reared on the tale of Rumplestilskin or maybe from teenage readings of The Hobbit. It could be from my more recent forays into Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden novels.

I know, I know - I never said I wasn’t a nerd.

Regardless of the origins of my belief, my theory was, in a way, proven earlier this week, when the New York Times ran a piece by Justin Wolfers entitled “Fewer Women Run Big Companies Than Men Named John.” In it, the writer created what he called a “Glass Ceiling Index” that looked at the ratio of men named John, Robert, William or James running companies in the S&P 1500 versus the number of women in the same role. His conclusion? For every one woman at the helm of a large company, there are four men named John, Robert, William or James.

To be clear: That’s not just one woman to every four generic men. That’s one woman for every four specifically-named men.

Wolfers’ study was inspired by an Ernst & Young report that looked at the ratio of women board members to men with the same ubiquitous monikers. E&Y found that for every woman (with any name) on a board, there were 1.03 men named John, Robert, William or James.

The New York Times article further showed that there are 2.17 Senate Republicans of the John-Bob-Will-Jim persuasion for every female senate republican, and 1.12 men with those names for every one female economics professor.

While all of that is certainly a sign that the more things change, the more they stay the same, it made me think about the financial world and our own glass ceiling.

In 17 years in finance, I have never once waited in line for the bathroom at a hedge fund or other investment conference. While telling, that’s certainly not a scientific measure of progress towards even moderate gender balance in finance. As a result, I decided it would be interesting to construct a more concrete measure of the fund management glass ceiling. After hours of looking through hedge fund & private equity mogul names like Kenneth, David, James, John, Robert, and William, I started referring to my creation as the “Jim-Bob Ratio,” as a good Southern girl should.

I looked at the 100 largest hedge funds, excluded six banks and large fund conglomerates that are not your typical “cult of personality” hedge fund shops, created a spreadsheet of hedge fund managers/founders/stud ducks and determined that the hedge fund industry has a whopping 11 fund moguls named John, Robert, William and James for every one woman fund manager. There was a 4:1 ratio just for Johns, and 3:1 for guys named Bill.

(c) MJ Alts

And even those ratios were generous: I counted Leda Braga separately from Blue Crest in my total, even though her fund was not discretely listed at the time of the 2014 list.

I also looked at the monikers of the “grand quesos” at the 20 largest private equity firms. There are currently three Williams, two Johns (or Jon) and one James versus zero large firm female private equity senior leadership.

Of course, you may be saying it’s unfair to look at only the largest funds, but I doubt the ratio improves a great deal as we go down the AUM food chain. There are currently only 125 female run hedge funds in a universe of 10,000 funds. That gives an 80:1 male to female fund ratio before we start sifting through names. In private equity and venture capital, we know from reading Forbes that women comprise only 11.8% (including non-investment executives) and 8.5% of partners, respectively. Therefore, it seems extraordinarily unlikely that the alternative investment industry’s Jim-Bob Ratio could fall below 4:1 even within larger samples. Ugh. One more reason for folks to say the S&P outperformed.

Now, before everyone gets their knickers in a twist, I should point out that I am vehemently NOT anti-male fund manager. The gentlemen on those lists have been wildly successful overall, and I in no way wish to or could diminish their performance and business accomplishments. And for those that are also wondering, I am also just as disappointed at the small (read virtually non-existent) racial diversity ratio on those lists as well.

What I am, however, as regular readers of my blogs know, is a huge proponent for diversity (fund size, gender, race, strategy, fund age, etc.) in investing and a bit of a fan of the underdog. Diversity of strategies, instruments, and liquidity are all keys to building a successful portfolio if you ask me. And, perhaps even more importantly, you need diversity of thinking, or cognitive alpha, which seems like it could be in short supply when we look across the fund management landscape. Similar backgrounds, similar stories, and similar names could lead to similar performance and similar volatility profiles, dontcha think? While correlation can be your friend when the markets are trending up, it is rarely your bestie when the tables turn. And if you don’t have portfolio managers who think differently, are you ever truly diversified or uncorrelated?

In the coming months and years, I’d like to see the alternative investment industry specifically, and the investment industry in general, actively attempt to lower our Jim-Bob Ratio. And luckily, unlike the equity markets, there seems to be only one way for us to go from here.

Sources include: Institutional Investor Alpha magazine, Business Insider, industry knowledge and a fair amount of tedious internet GTS (er, Google That Stuff) time.